|

I don’t know why my life all went wrong. It did, of course—and no, I’m not talking about this bloody war. That’s nothing I had to do with, nor anyone I know. It just happened, far as I can tell. I don’t doubt there are those who actually know, maybe down-the-line or way off in London. The colonel maybe knows, or the generals. The King should. God Almighty must. (Surely God knows!?) But I don’t. It’s too big for the likes of me. I ought to know about my own life, though, right? I mean, it’s my life. If I don’t know, I can’t expect anyone else to figure it out. Then again, I’m not so good at figuring. Never was. Book-learning isn’t for me.

I muddled through school, left as soon as might be, and was glad to go. I went to work on the Home Farm, as most Village boys do. A few wanted to work in the Castle itself; but being a footman or someone’s valet, pressing the master’s suit or handing him his hat? No, that wasn’t for me, either! I started as ploughboy, leading the horse. I cleaned off mud, mucked out stalls, and learned to groom and harness. Finally, I earned a full man’s wage, and took due and proper pride in every straight furrow.

No straight furrows out there in No Man’s Land.

You know, it’s hard to believe now, but all around here was farmland once. There was a village not a mile away, though everyone’s fled and the houses have been bombed to ruins. I think that over there may have been a potato field, or maybe corn. Now it’s just craters filled with mud and water. Out there is our barbed wire, and beyond that is their barbed wire; and in between is No Man’s Land. We’ll be going over the top again soon enough, or so we’ve been told. Meanwhile, I stand here on this box, looking out to see if they are coming first. We’ve been told to stick well up above the edge of the trench, not skulk down just peering over, because better it be your shoulder or chest than the top of your head blown off. At least then you’ll have a chance it’ll only be a Blighty one. Not that’s the way anyone wants to get home.

I had a long leave once. Troop ship across the Channel, train to London, change for Glasgow, up the line to Lochfoot, and along to Railway Terrace. Like all the others, I’d kept my pecker up with the good memories of home. So I stopped on my way from the depot, went into the butcher’s, and splurged my pay on a packet of pork chops. (We certainly never had the like of those chops here on the line, where it’s bully beef or beans, with plum-and-apple jam for pudding.) It was supposed to be a homecoming treat for all of us. Admittedly, it didn’t turn out quite like that; but that’s another story. Anyway, Ada fried it up; and I reckon our wee Jeanie never ate such a good meal in her life.

Ada took my eye in church. She was sitting up in the gallery with the other servants from the big houses on Lochview Crescent. A little woman, short and slight and almost dainty, her thin hair pulled back in a bun at her neck that looked so tight I longed to unpin it and let it loose—yes, and free her, too, from being locked behind the doors of Laurelbank. I wanted to take her out into the sunshine, kiss her till she laughed with joy, and bring her home to the first true family she could ever have known. What can I say? I was a young man in love. Once you’re wed, you live in the real world.

After we married, I took Ada home to Lilac Cottage, where I lived with my mother. “Only a second wife” Ada likes to call her; but she was all the Ma I ever wanted or needed. I suppose I was a change-of-life baby; all I know is my “real” mother died when I was born, and my older sisters were all grown and left home. So I was only a wee motherless babe when my father married my true mother. Hugh Robertson he was called, same as me. He was Head Forester on the estate. That’s a solitary job most of the time; and I prefer working with friends. My father never said anything against my choice to be ploughman—though, mind you, he wasn’t a man to say much ever, no more than I am myself. He died shortly after I left school; but the Duke (and the Duke’s factor, which was more important) never turned out a widow, beside which I was working on the Home Farm myself by then. So I was raised in Lilac Cottage, and never thought to leave it.

I don’t think my mother ever truly took to Ada. They do say two women cannot share a kitchen; and it may be that was the problem. It was, after all, my Ma’s kitchen, and had been ever since she wed my father. She had her habits, which I dare say were not the ones they’d taught Ada in that orphanage she was raised in.

Certainly, Ada never took to my mother. So I gave into her insistence that I take the job on the sidings. At least that finally made her happy—or as happy as I ever knew her. We moved to Railway Terrace; and she had a place of her own at last. And then our Jeanie came, which surely helped, for every woman wants children. Ada kept the house and child; I earned the wage that kept them both. I went back to the Village to see Ma every Sunday, with our wee Jeanie when she was born, so she’d know her Gran. It felt like coming home, for all that I lived now in a tenement house in the Terrace. My old pals, though, gave me little more than a “How’s it going?” There was little for us to talk about any more.

Work on the railway sidings was a different sort of job, I’ll admit to that much.

Of course, there was a gang of men I worked with there, just as there are fellow soldiers here in the trenches. I’ve always been the sort to make easy friends. That’s the best of this war, having pals to share it all with. As for the rest—well, you don’t really get used to the stink, though you notice it most when you’ve had a couple of days leave and come back fou on plonk. I’d hardly say your feet ever get really dry, except under a hot summer sun, when you sweat like a horse ploughing clay. Winter is cold; but I could say the same of Number Three Railway Terrace as far as that goes. There’s bugs in the blankets, and lice in your clothes; and no cleaning them out, for all that we try. You scratch in parts would have got you the strap back at school. Still, for all the things a lassie’d whinge about, there’s your pals here, too, right? We signed up together, we trained together, we serve in the trenches together, we go over the top together. If we’re blown to Kingdom Come, we do that together, too. But if we hang on the wire, we die alone.

A fair few have copped it; but there’s still Billy Mason and Joe McTaggart, both from the railyards. Eventually, we’ll beat Jerry and get home to a hero’s welcome, just you see. This war has been the saving of me, I reckon.

That may seem an odd thing to say. After all, it’s not over yet; and, who can say if it’ll wind up being the end of me. But there was a long time when I couldn’t see beyond the railway siding and enough beer at Pat’s on the weekend to drown the world. The army sobered me up, in more ways than one; and I suppose I ought to be grateful for that, though it seems perverse beyond belief to be grateful for a war that’s killed so many of my friends, and may yet kill me. One day, though, it’ll be over; and then they’ll send me home. God alone knows what’ll become of me then.

When I had that long leave, I spent every day at Lilac Cottage. Went up the Farm, too, had a natter with my old pals from when I was ploughman. I suppose every Jock back from the front feels that way when he’s home.

I write my mother pretty well every week.

I don’t write Ada.

God, the din’s enough to deafen you. It’s the guns trying to soften up the Krauts. I know better. Been around too long. All it does is tell Jerry we’re coming so they’ll be ready for us. The brass hats don’t seem to learn. Doesn’t matter if it’s Moaning Minnie gets you or a sniper. You’re dead either way.

It’s been going on a while now. I reckon the sergeant’ll be here with orders soon. The others think so too; I can tell. There’s Wallace checking his kit, and Scotty taking a last drag. And McTaggert’s gone to the cludgie for a pish again.

What was that? You can’t tell anything with these whizz-bangs. Between the noise and the flash, I wish the bloody guns’d

|

This story was written as a treat for my sister, Flo Watson, in the 2022

Worldbuilding fan fiction gift exchange. It was

posted to the Archive of Our Own on 17 March 2022 with the reveal on the 25th, and uploaded here on April 1st.

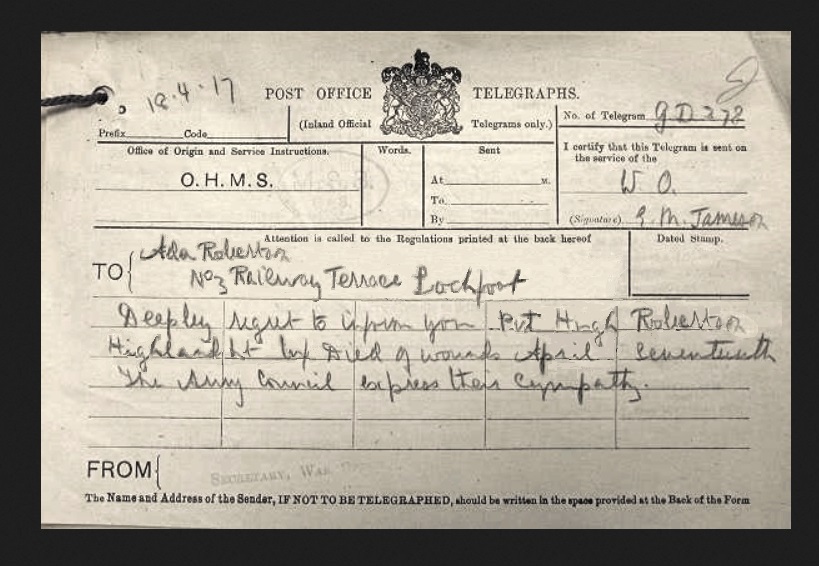

Jean’s father, Hugh Robertson, was probably in the Highland Light Infantry, like most volunteers from Glasgow. Some information about them can be found here. Their uniform included in a kilt in the MacKenzie tartan, which is the one used in this webpage design.

|

|

|

|

|